Strolling through the streets of Venice offers the lucky travelers the chance to see and admire many beauties of all kinds: canals and the rii with typical gondolas, historic buildings, wonderful churches. It is practically impossible not to get lost in so much wonder! And yet, there is a very characteristic world that escapes the eye. At least, to the eyes of those who stay down in the street.

Today I want to show you a Venice from a slightly unusual point of view, which was the scene of one of the scenes of the movie Mission Impossible 7 starring Tom Cruise filmed right in town: i will take you to the rooftops! Yes, because I firmly believe that every aspect of a place has something to tell us about its identity and that of its inhabitants.

The French ethnographer Marc Augé talked about two types of spaces: places and non-places. The former are characterized by social relationships, memories, traditions and belonging. The second are all those spaces that do not carry a sense of belonging, such as airports. Well, I think I can say that the roofs of Venice and the elements that characterize them belong to the so-called "places": the result of actions between people and interactions with the surrounding space and for this reason susceptible to change.

So come on, let's go up in search of chimneys, wonderful altane and suspended liagò!

The Venice of the 7000 fireplaces

Well yes, a rough estimate counts about 7000 fireplaces throughout the Venice!

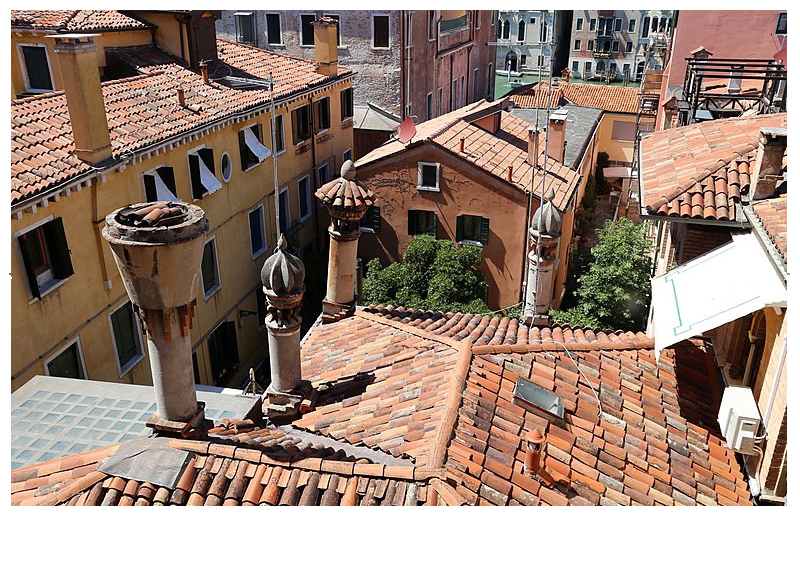

Now, who knows Venice, knows that the urban landscape is very dense: very close buildings divided by calle and callette minori. This gives, from the point of view of a roof, an interesting succession of chimneys with different shapes, some even a little unusual compared to those we could look at in other cities.

Obviously, these elements of minor construction were not born with the awareness that they would become elements so characteristic that they would be the object of study and admiration all over the world, but derive from the need to make the domestic environment healthier. In fact, before homes were equipped with fireplaces, there was the problem of heating the rooms on cold, damp winter days without getting intoxicated by smoke. Initially, the solution adopted was to light the fire in the house, leaving small openings in the roofs that would allow ventilation of the rooms. This ploy, however, involved a considerable dispersion of heat and allowed moisture to enter the homes.

So, for the Venetians, there was soon the need to create a structure that would at the same time allow the forced escape of smoke and that would safeguard the roofs, which at the beginning were built with straw, from the very frequent fires caused by burning sparks.

It is a fact that the first citizens of Venice began to design fireplaces and learned to do so with great skill, giving this element a very peculiar conformation compared to those present in other cities.

The construction of the fireplaces was immediately a matter taken very seriously, to the point that already in 1200 was established a School of Masons, that is, the builders, the material builders of these elements. And the importance of knowing how to build them to perfection is testified by the fact that the final test to obtain the mastery was, in fact, construction of a fireplace that met several criteria including the architectural style of the period.

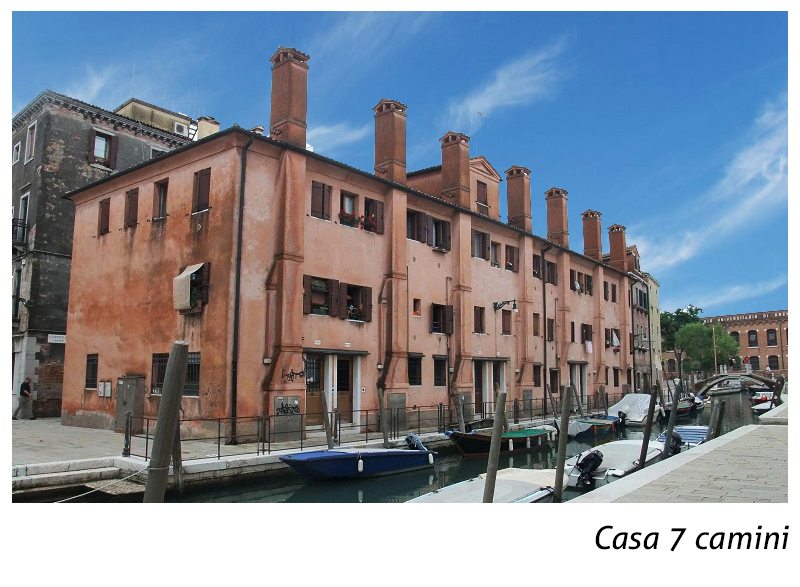

Looking over the roofs of the city we will notice that there is no single form of chimney. There are some in the shape of a bell, the most common, which has the shape of an inverted cone, such as those of Ca' Dario; in the shape of a cube, like those of Casa 7 Camini; in the shape of a fork, a shape brought into the city from the countryside of the Veneto hinterland. To these types were added around the middle of the Sixteenth Century the obelisk chimneys, sumptuous and elegant pinnacles. These, like those of Palazzo Mocenigo, later demolished, Palazzo Balbi, Palazzo Papadopoli, Palazzo Minelli and Palazzo Belloni, stood proudly on the noble buildings, then becoming characterizing elements of the entire construction. Wires were made inside, both for a matter of lightness and to allow the extinction of the sparks, while the smoke escaped from the openings at the base of the obelisk itself. Legend has it that these particular structures indicated the presence within the family to which the palace belonged of a "sea captain general": a belief in reality not true, since only the Balbi and Mocenigo families could boast captains in their lineage. Many of these fireplaces were destroyed over time because of their daring height they attracted the lightning that was able to hit them and therefore damage them. They stopped using this type of chimney, and on the remaining ones were installed real lightning protection devices that have allowed the transmission of these magnificent elements up to our days. Fortunately...

These are among the best known types to which must be added the changes made over time to each of them.

Element that united this triumph of shapes was the use of tiles or hats that served to prevent the infiltration of rainwater inside the chimney and the internal structure of the same that attracted the smoke in the chimney and conveyed it towards the side holes that pushed it outwards.

To embellish and make the chimneys even more precious were the decorations of artists of the caliber of Giorgione and Titian and the work of some great architects such as Palladio, Scamozzi, the Lombardo and Sansovino.

To whom I would like to remind of this picturesque scenery, I would like to recall the image of a figure closely linked to the chimneys, the scoacamini, the chimney sweep, from which the calla where they lived takes its name. A figure always soiled with soot that walked on the roofs of a majestic Venice.

The altane: the terraces on the roofs of Venice

"I do not feel like sleeping. Where can this stepladder, of which I glimpsed on the landing, take you as you enter my room, the first steps? Perhaps to some attic? Let's try it. I arrive in front of a door, closed by a simple bolt. I open it and find myself outside on a wooden platform, bounded by a parapet. This terrace, this lookout point, is on the roof of the Palace. From here I dominate the slope of its old tiles and I am close to its tall chimneys, one of which ends in the shape of a nut and the other in the shape of a funnel. What do I still see? A shimmering corner of the Grand Canal, the rounded dome of a church, then other roofs, other chimneys, all of this bathed by the glow of a shining moon...".

These are the words of the poet Henri de Régnier who, visiting Venice for the first time in 1899, described his first experience on the rooftops of the City, in particular the first time on an altana, that of Ca' Dario where he was a guest of the Countess de la Baume and Madame Bulteau.

Element belonging to what can be defined as a minor building, is certainly the altana: they are a kind of terrace consisting of a platform made of wooden slabs, supported by a series of small brick or stone pillars.

Since these structures are additions to the original building, the choice of construction materials had to meet two very specific requirements: lightness and resistance to environmental factors, such as salt. For these reasons, from the very first constructions, it was decided to use larch wood.

Over the centuries, the altane have maintained a certain consistency of use by citizens. They were the place of the house where people went to stendar la lissia, that is to say to hang out the laundry, taking advantage not only of the presence of the sun, but also of the air element that infiltrated between the wooden planks.

In the Renaissance, it was also a sort of beauty farm, in the sense that the Venetian ladies of the time loved to lighten their hair through the application of a mixture and the exposure of their hair to sunlight. To do this they used a sort of big hat, called solana, on which the hair was placed, a technique similar to the more modern shatush proposed by a well-known Italian air stylist! Did he perhaps take his cue from this completely Venetian custom?

Given the privileged position, the altane have always been a strategic point of observation of the parties to which we Venetians are very attached, including the Feast of the Redeemer. A more intimate way of participating, therefore, to share with family or friends.

Certainly is that over the centuries, the most frequent use of the altane is to enjoy a bit of sun and cool off during the sultry summer nights and why not, in the city of spritz, enjoy an aperitif in company!

For those who visit the city, but don't have the opportunity to enjoy at least one evening on the altana, there are restaurants, taverns and bars that offer their specialties on the altana, to ensure a pleasant sensory experience made of light, wind and breathtaking views.

After all, painters such as Vittore Carpaccio in The Miracle of the Relic of the Cross, Giovanni Mansueti in The Miracle of the Relic of the Cross in Campo San Lio, could not remain indifferent to this great fascination that the altane transmit.

Even the great playwright Carlo Goldoni in his work La Putta Onorata refers to this place in the house so much loved:

"Oh dear I am sol! Co lo enjoy it! Blessed be the Altana! At least if a puoco breathes. I, who don't know what is wandering through the hole of the house, would have died of melancholy, if I hadn't had this place".

The liagos of Venice: loggias suspended towards the light

If we look at Venice from above we will notice, looking at most of the palaces, on the highest floors,loggias that protrude from the buildings and delimited by windows on three sides: the liagò.;The term, according to the dictionary of the Venetian dialect of Giuseppe Boerio, derives from the Greek heliacon, i.e. place exposed to the sun.

In fact, in the city already with the first buildings, which were mostly built with wood according to the techniques of naval construction, there was the need for the Venetians to "capture" the sunlight that was struggling to settle the whole of the typical, but equally narrow streets.

The first evidence of such structures date back to the period between the twelfth and thirteenth century, although very often the term was used as a synonym for another type of structure more recent: the altana. It is a wooden terrace placed on the roofs of buildings and sometimes replaces them completely.

So, for example, in 1316, the Major Council decided to demolish the lairauts on the canal: probably this choice was determined by their instability and danger.

One of the best examples of this type of loggias can be found in Palazzo Falier Canossa, homes of doges and bishops, on the prospectus overlooking the Grand Canal. In this case the liagò are even two, placed at the two ends of the facade. They are two loggias of rather large size in reality, more than just spaces to capture the light are real rooms stretched out over the waters of the Canal. In a place certainly enviable!

Another famous example can be found at the Casino Venier or otherwise called Ridotto Venier, where it assumed a very unique function to discreetly spy on the passage over the Ponte dei Bareteri, below it. This use of the liagò was necessary due to the clandestine nature of these lounges where gambling, literary and musical activities were combined. Once again, a confirmation of how the places assume a particular symbolic value depending on the actions and interactions carried out within them, giving them an identity that goes beyond the structural characteristics alone.

In fact, generally, the liagò were used by Venetian ladies to enjoy the sun and to dry their hair. A use, this one, decidedly different from the one just described and which speaks to us of a domestic reality in which social relationships were shared in these small rooms warmed by the sun.

I could not fail to mention the liagò located on the second floor of the Doge's Palace. For those who want to try to imagine life in this area of the building, there is the possibility to visit it. Here, the patricians spent their time among the numerous sessions of the Grand Council walking and talking to each other. The ceiling, dating back to 500, is made of golden beams. On the walls there are paintings dating back to a later period, between 600 and 700. In this place you can admire three sculptural works by Antonio Rizzo depicting Adam, Eve and the Shield Holder.

Remember, when you are around the most beautiful city in the world do not forget to look at it with your nose up, because Venice will always find a way to surprise you!

Lascia un commento