"My only pleasure, therefore, was to graze on chimerical plans to recover the freedom without which I no longer wanted to live. All I did was think about escape because I was convinced that I could only do it by thinking about it."

These are the words with which Giacomo Casanova meditated on his escape from the dreaded prisons of the Doge's Palace in which he had been locked up, which had become extremely famous because it was shrouded in a halo of mystery, between reality and fantasy.

Justice in the Serenissima was something very serious! Considered incorruptible and absolutely impartial, he did not look at anyone's face, in the name of the most crystalline legality. The Republic, in fact, held a real hard punch against evildoers and criminals, of whatever social extraction they were.

The place where justice was administered was the Doge's Palace, where all legal proceedings were initiated, today we would say civil and criminal. It was enough to start a trial in Venice: in fact, it was enough an anonymous denunciation sent to the Palace in epistolary form, mailed in particular and scenic marble "mailboxes", with the appearance between human and monstrous. The cases were discussed and filed in the Chancellery Room, a rather austere place, which well represents its function.

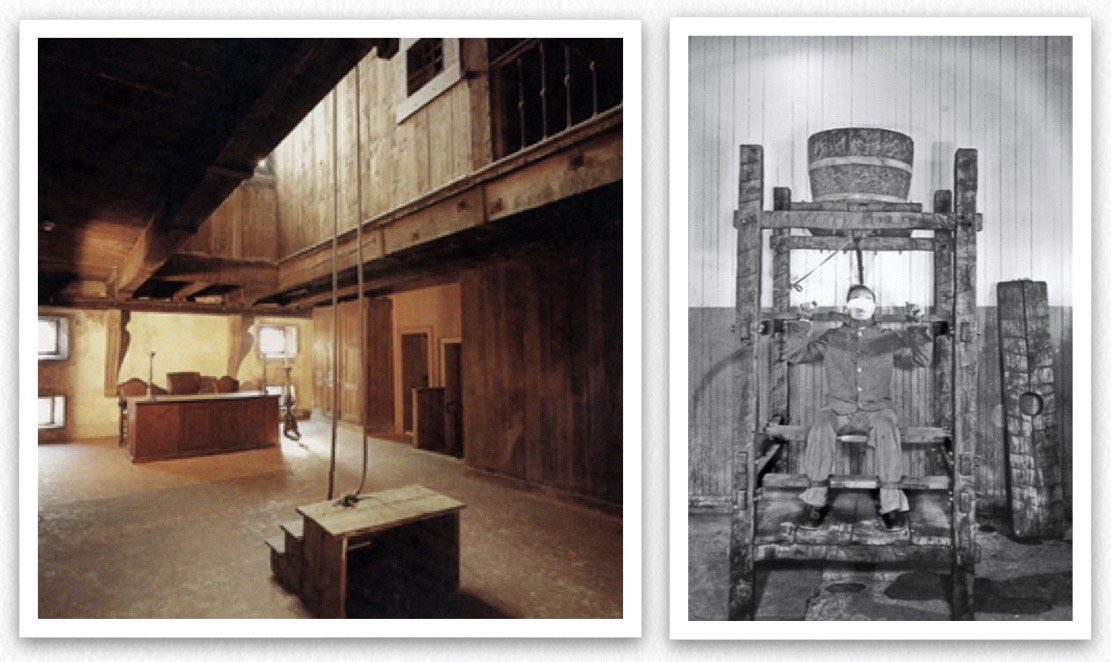

But the severity of Venetian justice manifested itself perfectly in what used to be the Torture Room: a narrow and frightening place, a wooden well on whose narrow balconies the cells of the prisoners awaiting trial opened. Here, in truth, practices were put in place everywhere in Europe, aimed at extorting confessions and truths to the sound of atrocious suffering. The most widespread was the string method to which the wrists of the prisoners were tied and slowly pulled up and hung in a vacuum, until they confessed. But the wickedness of the practice also had an indirect form: it was certainly no coincidence that the prisoners' cells looked out over this deep well, because in this way the screams of the tortured man could be heard loud and clear, frightening and thus speeding up the practice of admission of guilt, without any great waste of time. Diabolica Serenissima!

Also the torture of the drop was used a lot: the prisoner was immobilized to a chair, pulling his head backwards and a drop of icy water was dropped on his forehead. Always in the same place, with a very precise cadence. Over time this led to madness, and prevented the prisoner from being able to rest and sleep, then cooling the entire organism. The forced position then caused muscle damage and circulation problems, and if perpetrated for a long time this atrocious torture led to death.

One would have to wait until the 17th century to see these odious actions disappear little by little.

But where did the convicts who were found guilty and condemned end up? Obviously in prison! Every Sestiere had its own prisons, where minor crimes were served: for the debtors, for example, the gates of the prisons of San Marco were opened, located at the Mercerie, today's shopping street; the bad guys of war were instead locked up in the Gabioni di Terranova, where the Gardens of Napoleon in Riva degli Schiavoni are now luxuriant; and then there were the prisons of Rialto that arose when the Presidium of the Magistrates was established in the area.

But serious crimes were served in the most dreadful prisons of the Ducal Palace. Oh yes, because in the Doge's residence not only justice was administered, not only trials were held, but criminals were also detained, and these structures were undoubtedly the most difficult and difficult places in which to spend the years of imprisonment. Also in this case the nature of the crimes coincided with different locations: inside the Palace there were i pozzi (the wells), on the lower floors, i pozzi (the attic sinkholes), and since the 16th century the New Prisons, beyond Rio di Palazzo.

The wells, the hardest prisons

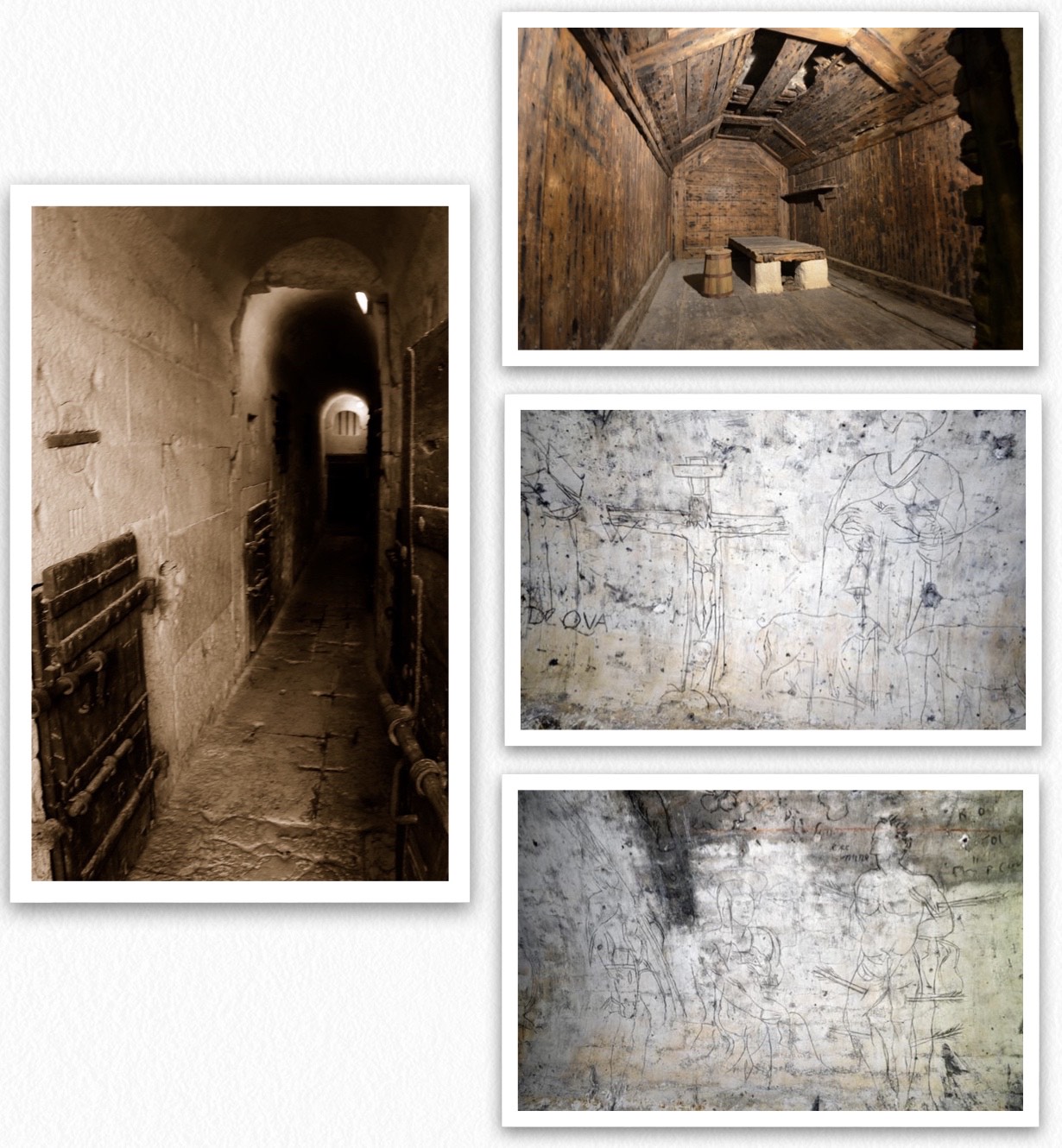

The wells were undoubtedly the toughest place to serve your guilt. Located on the lower floors of the Doge's Palace, they were accessed by a staircase near the triumphant Scalone dei Giganti, the important setting for the investiture of the Doges. They owe their name to their location inside the structure, that floor so low that on high tide days it flooded becoming a real well. But in reality there is no historical trace of this nickname until the 16th century, because these prisons were known as the prisons of the chief lords, later indicated as strong and then again as orb. The name wells only came out after the new prisons were built.

They were developed for 2 floors, and each had 9 narrow rooms. The structure was in "concentric circles": the cells occupied the central part of the floor, and all around it there was a corridor in which only the keepers circulated for the surveillance of the prisoners and the administration of food rations through small windows. This meant that the cells had no contact with the outside, no air and no direct light: the only light that reached them was from the square windows of the corridor. Too little to distinguish day from night, good from bad weather. These were all almost the same: small, narrow and with a vaulted ceiling, but so low that not all inmates were able to assume an upright position. And think that the average height at the time was much smaller than it is today.

The load-bearing structure was made of Istrian stone, big blocks and money, completely covered with larch wood boards, from the walls to the floor, often also the ceiling. The only "furniture" was a table used as a bed. The cells were identified with upside down Roman numerals, with some singularities: on the first floor the numbering went up to X (10) because the VI and VII (6 and 7) indicated the same cell, while on the upper floor there were only VI small rooms because 3 cells were used for another function: in April 1564 an infirmary was placed for the health care of prisoners.

Prisoners guilty of the most serious crimes were locked up in the wells, from where they did not always get out alive. For this reason many of them tried to leave a trace of their passage by carving wood or stone: it is easy to find, during the visit to these spaces, inscriptions and graffiti, legacy of the criminals locked up. Not only signs left by trembling hands, however, but also real wonders, works of the expert hand of an artist of the time. This is the case of cell X on the first floor where a real work of art was found with the restorations of the late twentieth century. It is a cycle of graffiti inspired by Venetian figurative art of the sixteenth century and represents, on one wall, the Virgin and Child surrounded by Saints Rocco, Sebastian and Benedict, while on the opposite wall is Christ on the cross with St. Rocco holding a bell accompanied by two pigs. The mosaic work is due to Riccardo Perucolo, a young fresco painter from Conegliano. In the middle of the sixteenth century he was locked up in the wells by the Inquisition with the terrible accusation of Lutheran heresy. The young man, however, did not stay there long in those prisons because he was terrified of torture and the inhuman conditions of the cells he confessed and was soon released. However, he had time to cheer up the stay of the other prisoners with his work, which remained for centuries under a thick layer of dirt, made with a nail to carve the figures on a layer of fresh lime and a brush soaked in water mixed with coal dust to fill the furrows. Freed from the wells, the artist lived about 20 years in the false faith of the Roman church, while continuing to believe in the reformist church: and this cost him his life, with a public stake in the Market Square of his city in 1568.

The Leads, for the inmates

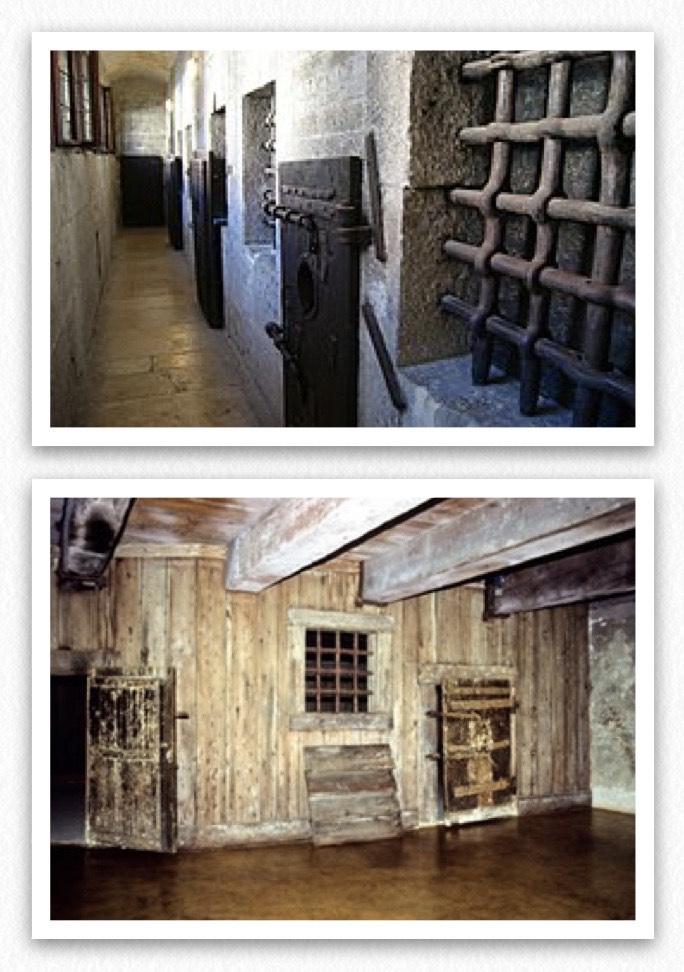

A better life was had by the prisoners locked up in the lead: they were the place where the nobles and prisoners of the Council of Ten served their sentences, or those guilty of short but not very serious crimes. These prisons were so called because of their location inside the Palace: they were in fact located above the Hall of the Three Chiefs, under the roof made of lead sheets. The construction of the sinkholes followed that of the wells: the Council of Ten, in fact, established that the Venetian justice needed a less harsh place of detention than the prisons on the lower floors, in order to lock up prisoners stained with minor crimes. The formalisation came with a decree dated 15 March 1591. However, they had a rather "short" life: only a little more than two centuries.

This prisons were divided into only 6 cells, made of larch wood partitions nailed together and made solid by strong iron elements. Their size varied between 2 and 4 meters per side. They too were placed centrally with respect to the perimeter corridor, and received indirect light thanks to the almost perfect correspondence of their windows with those of the attic, placed on the side overlooking Rio di Palazzo. But compared to the wells, they were also artificially illuminated at night. The ceiling, on the other hand, was not made of lead, at least not from the inside, but covered with wooden boards.

The social difference between the inmates here was quite clear: those of the lead were given certain privileges, such as the possibility of having objects delivered from the outside, furnishings, but also quality food and even flasks of good wine. They also benefited from a small dowry of money for their needs, which were then met by the caretakers, and medical assistance thanks to the presence of the infirmary.

Famous people were locked up in one of those cells, including Daniele Manin, Nicolò Tommaseo and Paolo Antonio Foscarini. It is thought that the place described by Silvio Pellico in "My Prisons" was exactly the lead, but in reality it is a different place, because he tells of a cell always placed in the attic but in correspondence of the Palatine Chapel. But in the common imagination the leads are associated with the name of Giacomo Casanova. The Venetian libertine was imprisoned here for a year and three months, from 25 July 1755 to 31 October 1756, accused of various crimes, such as fraud and fraud in gambling, which he loved so much, of Freemasonry, slander, witchcraft and certainly, knowing his vicious and unrepentant habits, even of libertinism. Thirty years after his imprisonment Casanova in his "Storia della mia fuga dai piombi" (The story of my escape from the leads) tells the most famous fact related to these prisons, that is his escape, between reality and licentious novel. The leads were considered an absolutely safe and escape-proof place. Yet on the night of October 31, 1756, Casanova, with his cunning and obstinacy, managed to escape. He narrates that during the previous weeks and completely "undisturbed" by prying eyes, he made a hole in the ceiling of his cell. On that famous night he crossed it and managed to reach the outer roof and here, like an expert acrobat, he reached a dormer window which then led him inside the Palace. Here, however, it seems that he had met a caretaker who did not recognize him and, on the contrary, mistook him for a visitor who had been locked up by mistake: he opened the big door and allowed him to go out quietly, unconsciously releasing a prisoner. And so, Casanova entered the Palace in handcuffs and walked out of the main door, in search of freedom and new unrepentant adventures.

Truth or fantasy? Well, who knows? But let's indulge in a bit of healthy romance and be seduced by the persuasive words of the great seducer Giacomo Casanova...

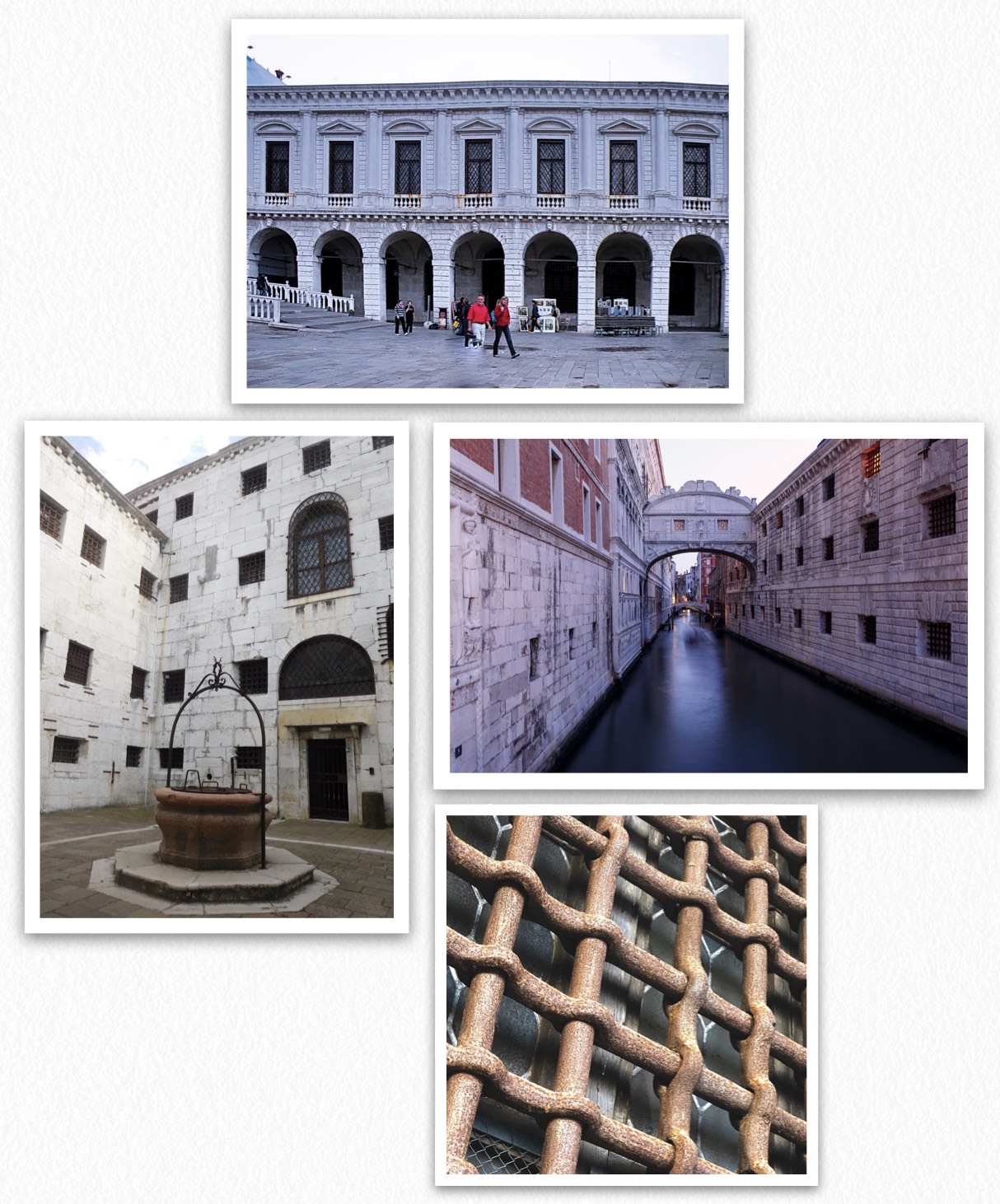

The New Prisons, the first state prisons

The prisons located inside the Ducal Palace soon proved to be insufficient for the ever-increasing number of crimes to be punished by imprisonment. Not only that. The foul-smelling air that came up from the wells and invaded an area of the courtyard began to become unbearable: the conditions in the prisons had become rather unhealthy and needed to be improved. It was therefore decided to build a structure exclusively dedicated to detention: thus the New Prisons were born, the very first example in Europe of a functional construction with State prisons as its destination. The choice fell on a space not far from the Ducale, the one beyond Rio di Palazzo. The structure was begun with a design by Giovanni Antonio Rusconi in 1563 and was then taken up by a famous architect of the time, Antonio da Ponte, who later designed the Rialto Bridge. The intent was to create a large structure, where the conditions of detention were better, ensuring ventilation and natural lighting, large and healthy spaces. This was ensured by the choice to create a large inner courtyard in an isolated building, free from all four sides, allowing light to penetrate from all sides. The building was not to have frills or ornaments but to represent its function well. It therefore had a very sturdy structure that let you feel the feeling of strength, while maintaining a discreet elegance thanks to Da Ponte's stylistic choices.

There were only two floors, with the main facade opening onto the Riva degli Schiavoni: a massive, high portico with seven arches of quadrangular pillars completely covered in Istrian stone ashlar, and as the only ornament the marble heads placed as a keystone. A corbelled cornice acts as a support for the second floor where each arch below perfectly corresponds to a wide and slender opening, each one enclosed by Doric semi-columns that find a greater momentum thanks to the presence of pedestals. They close the plane of the small balustrades with small columns and arched tympanums alternating with triangular ones, to dampen any feeling of monotony. Everything is closed with a large corbelled cornice. The façade rising from the waters of Rio di Palazzo is reminiscent of a real fortress: three orders of small square windows in a wall characterized by a simple rusticated design with horizontal bands that amplify the trend and strengthen the perspective escape towards the Ponte della Canonica.

All the openings, both internal and external, are equipped with sturdy gratings, and I suggest you to take a closer look at them because they are presented with a truly singular and fascinating metal weave, as if they were a fabric magnified by a microscope. Think that they were not placed at a later time, but were mounted during the construction: they were inserted in their base and the rest of the building was built practically around them. Thinking of unscrewing or cutting them is completely impossible, a clear sign of strength on the part of the Serenissima. Behind the grilles of the portico on the ground floor there was a large common cell called Justinian's cell formed by two small rooms, the castle and the city, each of which was able to accommodate about twenty prisoners.

Inside the building there were such a number of cells capable of accommodating up to 400 prisoners: the division was strict and followed the hierarchy of the seriousness of the crimes committed.

All the prisoners enjoyed the fundraising that the Brotherhood presided over by the Patriarch instituted in their favour, to alleviate their sentences.

Within the structure there was also the Magistracy "the Lords of the Night at the Criminal", made up of six members, each representing a sestiere, with duties of surveillance, police and institution of trials.

The prisoners arrived at the New Prisons after they had been tried in the Ducal Palace: for this reason a direct connection between the new and the existing building was created. And the connection is nothing more than one of the emblems of Venice: the Bridge of Sighs. Completely covered with wood inside and divided into two separate corridors, one in each direction, it owes its name to the sighs drawn by the prisoners when they saw the outside world for the last time. Reality or poetic legend? Legitimate question because in truth from the windows of the bridge you can see very little of the Lagoon and the "external" Venice. Certainly he saw more tears than smiles.

Today defined as the bridge of lovers. Yes, but in love with the lost freedom...

Lascia un commento