In the heart of Venice, in Saint Mark Square, between Saint Mark’s Campanile and the pier, an eminent palace overlooks the Square: that is the Marciana Library. This building is fundamental to understand a tessera of Venice’s history, since it is the tangible evidence of a past rich in culture. Its shapes, made of Istrian limestone, enshrine a story of an educated oligarchy, which waves together with the genius of artists and a deep commitment for the city of Venice.

The Marciana Library is considered a masterpiece for several different reasons. First of all, it is one of the biggest ancient libraries in Italy and it hosts an extremely significant collection of classical texts. Moreover, with its architecture, both majestic and light, it is considered a key architecture of the Venice Renaissance and the most important work of its first architect, Jacopo Sansovino. Finally, it represents also a specific reality, a precursory perception of culture, typical of just Venice and its aristocratic families.

Towards a public fruition of cultural heritage

The history of the Marciana Library started in 1362, when Francesco Petrarca, willing to donate his collection to the Republic of Venice, designed a project for a public library which was supposed to exhibit the treasures he gathered during his whole life. His plan was innovative, since back in the days collections were privates and the owners used to keep them exclusive and inaccessible. Yet, the poet’s request did not get satisfied and he ended up devoting his belongings to the city of Padua.

A similar request appeared again in 1468, when the cardinal Basilio Bressarion donated his collection of more than 800 Latin and Greek manuscripts to the Republic of Venice. As Petrarca, he stipulated the establishment of a public library, accessible to the entire community. This event was the symbol of a new trend investing the aristocratic oligarchy of Venice. The Venetian elite developed a new way of considering its artistic and cultural heritage. It understood the social and political value of art and it demanded public fruition. Wealthy educated families started to make their collections available to the community, in order to boost their status, to glorify their origins and, last but not least, to enhance the image of their city, Venice itself. Yet, such changes are usually slow and, in fact, at first, the cardinal’s collection was stocked in the Doge’s Palace and little was done to facilitate public availability. Books were organized one atop of the other in small rooms and some codices were even found being sold in local bookshops.

Finally, the time for the construction of a library arrived. At the beginning of the ‘500, the Doge Andrea Gritti promoted the Renovatio Urbis, the city’s project of renewal and the library was part of it. The Doge aimed to heal Venice’s spirit after a tough period characterized by both a loss in political influence and a war defeat in the Italian Wars. He was determined to glorify the city and to restore its international prestige, elevating it as a hub of learning and culture. Therefore, he planned a significant transformation of the urban architecture, which culminated in Saint Mark Square. From a Medieval centre characterized by food stalls and vendors, it turned into a luxurious classic venue.

So, in 1529, the architect Jacopo Sansovino was nominated “proto dei Procuratori ”, a sort of chief architect and urban manager, and put in charge of the project. The Marciana Library resulted the cornerstone of his project and has been assessed Sansovino’s masterpiece. Believing himself in the public fruition of all the artistic goods of the Church and the Republic, he started the construction of the library in 1537, to finally offer an adequate house to Bressarion’s collection and a public library to the citizens of Venice.

Unfortunately the construction works did not proceed smoothly. The first issue was related to the presence, in the selected area, of several stalls and hostelries, which needed to be relocated somewhere else in town. Once Sansovino fixed the problem, he had to face another major hitch: the heavy vault of the library collapsed, he was accused and sentenced to jail. Once he paid the bail, the architect had to deal with the interruption of the works due to the relocation of the meat market, the source of income essential to fund the city’s renovation project. Finally, in 1570 the architect died and the Library was not completed yet. The works restarted in 1582, when the architect Vincenzo Scamozzi was nominated to oversee and complete the project. Even though Scamozzi cannot be called “the father" of the Library, his contributions to the project are commendable.

Eventually, in 1603 the building was proclaimed “Official Library of the Republic of Venice” and it offered to the public one of the greatest collections of classical philosophy. It preserved Latin, Greek and even Oriental manuscripts, thanks to the commercial trades with the East Venice was famous for. Still today, valuable ancient pieces can be found at the library, such as the first book printed in Venice in 1481, ancient maps and atlases, the Breviario Grimani and the valuable ancient copies of Homer's Iliad. Moreover, the library has never stopped collecting books to maintain its prestige, indeed, it keeps acquiring both modern and precious pieces.

The facade as expression of Venice’ spirit

The polished white façade is not just a sublime pinnacle of Renaissance architecture in Venice, but also the material representation of the city’s devotion for culture. The building is elegant and homogeneous and with its series of forty-two arches split in two storeys, creates a strong visual impact. Sansovino got fascinated by the theatrical atmosphere of Venice and he transferred it into the façade, blending together, in a harmonious dance, light and dark, solids and voids, relief and simple limestone. The outcome is a theatrical scene of images and architectonic structures, pleasing the view at every glance.

More specifically, the façade is characterized by a long series of arcades over an exterior gallery, where the assemblage of structural elements results perfectly balanced and spectacular. The ground floor is characterized by a succession of columns in Doric style, alternated by a series of arches resting on pillars. The second floor follows the same rhythm, with Ionic style columns arranged on a precious balustrade with small columns, and enclosing high windows with round arch. The two rows of columns sustain richly adorned friezes: on the first floor decorated by beautiful festoons with putti and window openings and on the ground floor with trygliphs and metopes, recalling the ancient tradition of Doric architecture. The arches and the under-arches are teemed with different reliefs of male and female figures, lion heads, pagan divinities, mythological scenes and Greek allegories, so as to reference Roman models and, therefore, to convey a sense of authenticity and connection with the past. The external architectural composition is completed by a balustrade with sculptures of classic divinities, heroes of antiquity and three obelisks. The classical and elegant result expressed a precise message: the library was linked with the great civilizations of antiquity, and so it was Venice, which consequently claimed to be their natural successor and centre of wisdom and learning.

The powerful visual impact of the exteriors had also to communicate with the other important buildings in Saint Mark Square, especially with the Doge’s Palace in front it. Sansovini managed to harmonize perfectly the two buildings, which are so different in agese, styles, proportions and purposes, yet so alike in their ways of interpreting the Venetian conception of art and architecture.

The ascension to wisdom

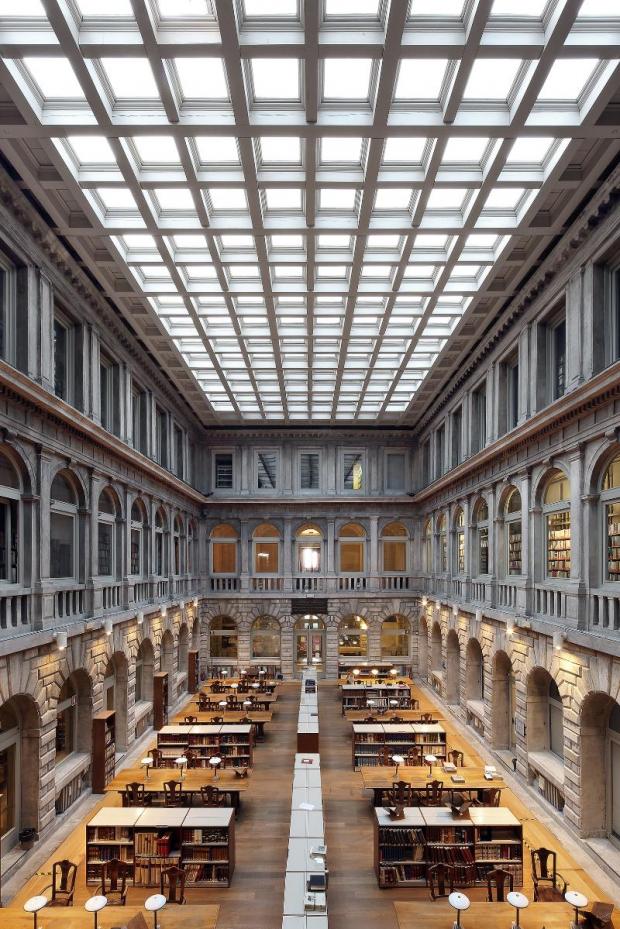

The interiors are as meaningful as the façade.

The staircase, the vestibule and the reading room are connected together through walls and ceilings decorations, in a unique and expressive narrative. The decorative programme involved the participation of some of the greatest Venetian painters of the late Renaissance, such as Titian, Tintoretto and Paolo Veronese, and it reflected the Venetian aristocracy’s interest in philosophy, culture and studies.

The staircase, composed of four decorated domes and vaulted ceilings, shows the Neo-platonic journey of the soul’s ascension, through culture, to perfection. While climbing up the stairs, also the soul elevates itself, through the practice of virtues and study, to finally reach wisdom, represented by the artist Vittoria, as a woman brandishing a book and a ring, symbol of eternity.

The staircase conducts to the vestibule. This was, at first, conceived as a lecture hall, yet, in 1591 it turned into the “Statuary Museum of Republic”, in order to host the collection of Greek marble statues, donated to the Republic by the cardinal Giovanni Grimani. He specifically demanded his collection to be placed near the library, to enhance a continuity between his collection and his grandfather’s one, already placed in the reading room nearby, together with all the other books and manuscripts. Scamozzi, renovated the vestibule, eliminating the previous decorative programme and adding frontons, niches, pilasters and cornices, in order to create a space suitable for sculptures. From the previous decorative programme of the vestibule, Scamozzi saved Titian’s work The Wisdom, in the ceiling, recalling the theme of wisdom of the staircase.

Once ready, the Grimani Statuary was one of the first collection of ancient sculptures to be available to the public, an epic event in the story of museums as we perceive them today. The Statuary lasted only for two centuries, then it was moved almost entirely to the Archaeological Museum of Venice, yet, the room did not lose its appeal, and today it is possible walking through this orange-warm gallery, admiring a harmonious fusion of busts, sculptures and architectonic structures.

Through the vestibule it is possible to access to the reading room, the hub of the ancient library. Here, at the beginning the space was filled with wood benches, for reading purposes, with the library’s books chained on top. Moreover, the decorative programme of the room, in connection with the previous spaces, was a journey through the intellectual realm and it represented philosophy, wisdom, learning and wise uses of knowledge.

However, during the centuries, the space has been transformed several times and so was part of the pictorial decorations. On the walls, it is still possible to admire oil paintings of philosophers in niches, some of them painted by Paolo Veronese and Tintoretto. The ceiling is a stunning “Manifesto of Venetian Mannerism”, with twenty-one painted roundels inserted into gilded frameworks and surrounded by fifty-two elegant grotesques. Many artists contributed to the creation of the rounded paintings, among them, the most famous ones were Paolo Veronese, Andrea Schiavone and Giuseppe Salviati.

.jpg)

The Library, as mentioned above, faced many transformations. In 1811 was transferred to Doge’s Palace, then in 1904 to the former Mint and ultimately, it returned back to the origins in 1924. Yet, today the reading spaces and books’ depot are at the Mint, whereas the vestibule and the reading room turned into a museum and exposition venue.

Nevertheless, the sense of solemnity still lingers across the building. It is still possible to feel the weight of generations of intellectuals walking by, aristocrats donating their collections to public use and challenged artists adorning the spaces. The Marciana Library is the place to celebrate Venice as an ancient centre of wisdom and culture.

The access to the Marciana Library is from Piazzetta San Marco 7.

The days and times of entry are as follows:

- Monday - Friday: 9.30 a.m. - 3.30 p.m.

- 24 and 31 December: 9.30 a.m. - 13.30 p.m.

The Library is closed on the following days:

- Every Sunday

- January 1st and 6th

- Easter Monday

- April 25th

- May 1st

- June 2nd

- August 15th

- November 1st and 21st

- December 8, 25 and 26

Lascia un commento